From above, circling in a helicopter, the Jakobshavn Glacier resembles a turbulent ocean frozen in motion. Jagged peaks of ice jut out like whitecaps, forming wall after wall of serrated waves. They’re discolored with swipes of gray — sediment slowly scraped away from surrounding rocks — and fringed by blue cracks and crevasses. Cerulean streams of meltwater etch a web of rippling channels atop the icy mass.

It’s easier to sense the true magnitude of the glacier face from the ground. The frozen water rises more than 200 feet into misshapen points and then curls into a gentle slope next to where the helicopter has landed on barren dirt. Trickling meltwater makes its way through the ice, its gurgle punctuated by reverberating booms as a mass of ice breaks off (or calves) nearby, sending rubble tumbling with a splash into the icefjord.

The Jakobshavn Glacier dumps into an outlet north of the Arctic Circle in western Greenland. Called Sermeq Kujalleq in the local tongue, it’s one of the world’s fastest-flowing glaciers, moving more than 100 feet per day as gravity guides the river of ice to the sea. Its prolific calving produces 10% of the island’s icebergs — the chunks of ice that break off and float in water — and is believed to have birthed the iceberg that sank the Titanic.

The sights and sounds of the landscape are both beautiful and ominous. It’s part of the Northern Hemisphere’s only remnant of the most recent ice age — Greenland’s ice sheet — an otherworldly ode to the planet of the past. And it’s in the midst of catastrophic change.

John Englander knows better than most. As the helicopter stalked the glacier from the air, he had pointed to an outcrop of rock. When he hiked there more than a decade ago, it was drowned in snow and ice. Its dark gray surface is now eerily blank, any cover since melted away. He noted the trim line in the cliff above, marking the height at which the glacier once eroded the rock as it flowed. Today’s ice is at least 30 feet lower, Englander estimates.

According to satellite tracking, it took the glacier 100 years to recede eight miles leading up to 2000. From the turn of the century to 2010, it ebbed nine miles. “Each year, this glacier is just retreating further and further,” Englander says forlornly. If you ask him how Greenland overall has changed since his first trip there in 2007, his answer is short: “Melting.” And that has worldwide repercussions.

Greenland has become a hot topic of global discourse with President Donald Trump’s repeated desire to acquire the world’s largest island. It has been around for 3.8 billion years, home to the Indigenous Inuit peoples for centuries before officially becoming an autonomous Danish territory. About 80% of Greenland is covered by an ice sheet that’s more than a mile thick on average, holding 10% of the world’s ice. That ice — which holds about 24 feet of sea level rise — is disappearing.

More than two-thirds of Earth is covered in water, and it’s this resource that connects hot, humid Florida to icy Greenland. With its low elevation and 8,436 miles of coastlines — the second-most in the country behind Alaska — Florida is especially vulnerable to the sea level rise produced in Greenland and beyond.

Amid that looming threat comes an advocate: Nova Southeastern University, whose main campus is in the Fort Lauderdale area, wants to position itself as the state leader in sea level rise research, data and communication. It started with its merger this year with the Rising Seas Institute — the Florida-based nonprofit headed by Englander — but the combined team has far grander aspirations. A July trip to Greenland helped set those plans in motion.

“Greenland is really ground zero for sea level rise. Where the warming is happening the fastest is in the Arctic,” says Sharon Gray, associate director of the Rising Seas Institute. “That’s going to mean higher seas. There’s just no way around that … Meters of sea level rise — that’ll completely reshape a lot of Florida.”

AN INSTITUTE ARISES

In 1971, Englander was teaching a scuba diving course in the Bahamas when, 206 feet below the water’s surface, he discovered the remnants of an ancient beach. The flat, sandy patches wedged between corals, sponges and limestone showed where the sea level was about 11,000 years ago.

It was the first time Englander grasped the sea’s history of extremes. “We think of the shoreline as permanent,” he says. That memory followed him throughout his diving career, in which he grew the Underwater Explorers Society, or UNEXSO, into one of the largest sport diving operations in the world over two decades in the Bahamas. “Every time I went deeper in diving, I would look for signs of those ancient shorelines. But I still never thought (sea levels) would change in my lifetime.”

Climate change is complex and, often, controversial. The Rising Seas Institute rallies around sea level rise, one of its more digestible impacts.

Englander’s foray into the world of climate change could be called nontraditional by some, as his background is predominantly in business. After briefly leading The Cousteau Society in 1997, he ran the International Seakeepers Society, a Coral Gables-based nonprofit empowering the yachting community to contribute to oceanographic research, conservation and education. He has also offered consulting services to the marine and tourism industries as well as corporate and government clients.

His first trip to Greenland was in 2007, when he traveled with International Seakeepers stakeholders to witness Arctic melting in person. He recalls having an epiphany as the mechanics of climate change clicked into place: Just as sea levels have responded to global temperatures for millennia, rising as ice melts, it’s only logical that they’ll climb if the Earth gets hotter. Only now, civilization has laid claim to those vulnerable coastlines.

“It’s just so clear and powerful. I said, ‘That’s going to change the world,’” Englander recounts. “‘That’s a wow story. And I think I know how to teach that to people.’”

Along with sparking the idea for his first book, “High Tide on Main Street” published in 2012, the visit introduced Englander to trip leader Robert Corell — a pioneering Arctic scientist who had been leading group expeditions to Greenland since 2001. Their fast friendship became a working relationship when the pair established the first iteration of the nonprofit Rising Seas Institute in 2017.

Climate change is a complex phenomenon. And it’s controversial: Never before has the world had so much data about future hazards but disagreed so much about what to do about them. The Rising Seas Institute’s strategy is latching onto one of the most well-documented and tangible impacts — sea level rise — as an educational avenue. And what better place to communicate the threat than in Florida?

Following in the late Corell’s footsteps, the nonprofit still brings travelers to Greenland to see climate change firsthand. Including Corell’s initial trips, the organization estimates it has whisked hundreds of visitors to the remote island. Greenland is the institute’s home away from home.

If Englander is the public face of the Rising Seas Institute, Gray is its inner brains, creating educational content and coordinating its programming.

She has been an environmental activist since she hosted bake sales to save acres of the rainforest as a kid. Her background in marine science has taken her to jobs with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Mote Marine Laboratory, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute and the Florida Aquarium.

Gray met Englander in South Florida when he was writing his first book more than a decade ago. She has been working with him ever since. “There’s a lot of synergy between my background and his background and what he was wanting to do,” she says.

Slowly but surely, their influence has grown.

In 2020, the Rising Seas Institute wrote to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change contesting its omission of projected ice melt in Antarctica — a looming threat that hasn’t awakened in full force yet. Dozens of prominent researchers signed the letter, quickly leading the institute to publish a scientific paper challenging the IPCC’s conservative worst-case scenarios for sea level rise.

In its March 2023 sixth assessment report, the IPCC incorporated the Rising Seas Institute’s paper and cited it.

“There’s a good reason to only include what you can prove with a high degree of certainty,” Gray says. “But it just doesn’t give (readers) the big picture of what’s really going on. That was kind of the idea behind the Rising Seas Institute — to be a vessel for that.”

UNIVERSITY TAKES THE REINS

In 2022, a New York Times piece by Bret Stephens — a Pulitzer Prize-winning conservative columnist — caught the attention of Steve Halmos. A trip to Greenland with Englander had turned the well-regarded writer from climate skeptic to believer.

Halmos was a prominent Fort Lauderdale businessman looking for his next adventure. Stephens’ story inspired his own trip to Greenland through the Rising Seas Institute in 2023.

“I wasn’t a climate change skeptic,” Halmos says. “But when I came back from the trip, I too believed more strongly in the inevitability of sea level rise” and its implications for Florida. He points to his own waterfront backyard, where he’s noticed the waterline creeping up inches over the past three decades. “I think everybody who goes comes back a believer that sea level rise is heading our way.”

On the trip, he also learned that Englander lived in Boca Raton. As a member of the NSU Board of Trustees — the school’s Halmos College of Arts and Sciences was named after him in 2015 — Halmos saw an opportunity for synergy: What if NSU took on the Rising Seas Institute and its mission?

The eventual result, after much conversation and planning, was merging The Rising Seas Institute with NSU. The move was made official this January.

The institute slots into the school’s recent push called NSU Ocean, which harnesses the university’s high concentration of water-focused researchers and integrates that educational theme into all 13 academic colleges. Currently, 30% of all NSU’s funded research relates to the marine and ocean sciences.

Interestingly, Greenland isn’t very vulnerable to the sea level rise it creates. Its steep, rocky shorelines guard its inland much better than Florida’s flat, sandy beaches. As its heavy ice sheet melts, the territory will rise with the lighter load.

“The Rising Seas Institute, obviously, fits perfectly within that initiative,” says Ken Dawson-Scully, NSU’s senior vice president and associate provost for its Division of Research and Economic Development. “For students that are interested in (water-related) research, NSU is a national leader. NSU is investing into that continuously.”

The merger with NSU will allow the Rising Seas Institute to grow even more, Gray hopes. The university’s resources and credibility elevate their mission, put them in front of a multidisciplinary audience, and create a platform for potential climate solutions.

Gray’s and Englander’s aspirations at NSU start with integrating sea level rise education across departments to foster interdisciplinary understanding. They hope to organize a conference in Florida to better define worst-case climate projections, as well as develop international speaking and outreach opportunities to disseminate the information. They also want to expand their Greenland educational programs and create a policy center.

“I thought it was a perfect fit, and I still do,” Halmos says. “I’m even more convinced of that now as I know John and I know where the university is headed.”

THE TOP OF THE WORLD

A few hours by boat north of the Jakobshavn Glacier, the Eqi Glacier stands sentry. Stay for 20 minutes, and it’s easy to see why it’s also known as the calving glacier.

Its two-plus-mile-wide face is one of the most active calving sites in Greenland. The deep, echoing rumbles of ancient ice severing into icebergs rival even the fiercest Florida thunderstorms. Watching the chunks crash into the water, sending mighty swells across the fjord, can’t compare to the typical waves lapping the Florida coast. Several boats drift nearby, including one holding the first cohort of NSU’s Rising Seas Institute expeditions.

The scene is ethereal but, admittedly, a bit frightening — like some divine rapture roiling from the glacier in snippets. That’s the whole point of the trip: witnessing the impacts of climate change firsthand and, more importantly, tying those impacts to our home state.

“What’s happening here in Greenland is directly impacting us in Florida. But it’s so far apart that when you hear about Greenland, you don’t make that connection,” says Katherine O’Fallon, executive director of the Marine Research Hub in South Florida. “Seeing that today was a big deal. Visually, you can’t deny that. You can’t. How do you talk that away? How do you justify and say that’s not happening when you actually see it?”

NSU invited Florida Trend on the trip, alongside O’Fallon and other attendees, and covered some of the costs. The “fact-finding expedition,” as the university advertised, paired hands-on excursions with daily briefings that educated participants on the nitty-gritty mechanics of sea level rise (see “Sea Level Rise 101” on page 69). It also included virtual chats with subject-matter experts affiliated with the Rising Seas Institute who specialize in glaciology, national security and more.

Englander and Gray also focused on the aftermath of this damning realization: At this point, some magnitude of climate change is inevitable — what now? In their words, it’s time to understand, plan and adapt for a new era of sea level rise.

The team faces an uphill battle amid today’s politics, where climate change is often seen as a partisan divide. Last year, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed legislation that erases most references to climate change from Florida state laws. On the national scale, the Trump administration has recently announced plans to redact the endangerment finding, the legal basis for federal climate regulations under the Clean Air Act. It has also altered or removed climate-related materials on government websites, including legally mandated National Climate Assessments and the federal climate change research site. This May, the National Snow and Ice Data Center announced it was scaling back public-facing data products focusing on sea ice, retreating glaciers and snow accumulation.

But where there are gaps in scientific data, NSU President Dr. Harry Moon sees opportunity.

As the federal government makes climate-related data less accessible, the university could offer a public-facing repository with information to fill in the blanks, with a particular focus on sea level rise given the Rising Seas Institute. NSU could help centralize the many different throngs of research, much like a scientific literature review, to provide greater clarity and, hopefully, greater consensus on how to move forward together.

“This is not about politics. This is not about money. This is not about profit. This is about solving the problem that we have the capacity to solve,” Moon says. “It’s about credibility, being honest brokers. … We become the aggregator, the compiler.”

That idea — and more — popped up during impassioned discussions throughout the July trip. Some were ambitious. Attendees mulled over, for example, an international research consortium featuring coastal universities and their sea level rise research from around the world. (Moon says he’s aiming to have an initial assemblage of potential partners by next summer.) An NSU data logger, or better yet, a satellite campus or research facility could live on Greenland. Annual trips to the island could help attract funders to finance these goals.

The mission is especially important in Florida, where more than half the state’s 400-plus municipalities could be affected by as much as 6.6 feet of sea level rise by 2100, according to a 2023 study by researchers at Cornell University and Florida State University. Chronic flooding would threaten almost 30% of their local revenues, the study predicted, and the state would lose $619 billion in assessed property values plus their $2.4 billion in annual property taxes.

NSU’s path ahead is still riddled with unknowns. But its summer trip to the ice at the top of the world seemed to set a fire beneath the team.

“This is the last day of the trip,” Moon says over a cup of iced coffee at a Greenland hotel in Ilulissat, where shrinking icebergs are visible from the nearby window. “I say this is the first day of the beginning.”

Vanishing Legacy

As an Inuit skipper with Albatros Arctic Circle, Niklas Thustrup Johansen sees evidence of climate change every time he’s out on the water in Greenland — even at the ripe age of 23.

As a kid, his family took advantage of the wintertime sea ice for ice fishing. Now, he could sail all year if he wanted to. The seasonal ice is thinned or nonexistent; icebergs no longer fully shutter the nearby fjord.

“I’m a father. I have a daughter, and she’s only 6 months” old, he says. “I love nature, I love to hike, I love to sail. I want to have my daughter experience that as well, so I really hope she will see it before it’s all gone.”

Shattered Traditions

Naduk Heilmann, an Inuit 21-year-old working as a tour guide in Ilulissat in Greenland, recounts how heavily her family has traditionally relied on sea ice. In the winter, they would go hunting on the ice with their Greenlandic sled dogs for seals and polar bears.

As the world has grown warmer, that ice has grown less reliable. Heilmann recalls a friend’s family member who fell through thin ice mid-winter on his dog sled. He died.

“We are hugely affected by the melting of the glaciers, especially as Indigenous people of the north,” Heilmann says. “Global warming has changed our way of life.”

World Afloat

Frank Larsen moved to Greenland as a teacher from Denmark in 2004. Nine years ago, he made the switch to tourism. He now owns and operates Diskobay Tours in Ilulissat with his wife.

Over time, he has witnessed sea ice decline around the Greenland coasts, even disappearing altogether in some areas. If it does form, it doesn’t stick around as long as it used to. Larsen used to take tourists dogs-ledding across the nearby ice over the winter. That has grown impossible in the past five years. He has also seen the very glaciers he shuttles tourists to and from slump lower with melt.

It doesn’t always negatively change life in Greenland, he admits. “Everything’s a lot easier when the sea doesn’t freeze and when it’s only minus-20 instead of minus-30 (degrees).” Residents can fish year-round without being plagued by sea ice.

But he knows the changes here will have ripple effects. “The impact in Greenland is not that big. You see all the changes here, and they are changing fast, but the impact itself on people is not happening here. It’s happening all the places in the world.”

Sea Level Rise 101

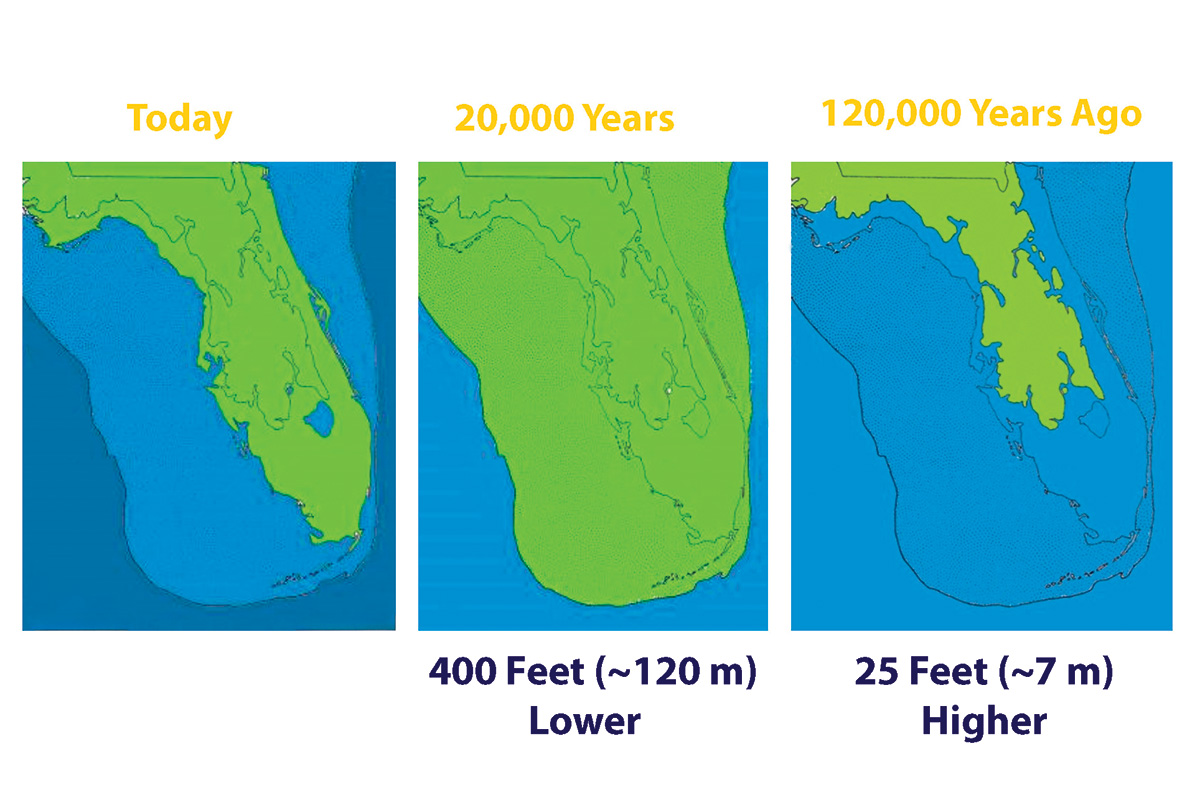

Sea level rise is not a new concept: For millions of years, Earth has gone through cycles of warming periods and cooling periods, or ice ages. The patterns are driven by variations in the planet’s elliptical path around the Sun. As temperatures rise and fall, sea levels have fluctuated by hundreds of feet. Warming periods melt ice and expand seawater, pushing oceans higher, while cooling periods freeze water into ice, lowering seas again. The well-documented processes have happened in parallel for millennia.

Within the last century, though, the climate has broken out of this cycle. Earth is supposed to be entering the next ice age. (Air bubbles trapped in ice cores, the ice samples drilled from up to two miles deep in the Greenland ice sheet, reveal clues about ancient climate patterns.) But Earth’s temperature has risen by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1850. The 10 warmest years on record have all occurred in the past decade.

What changed? Human impact.

Since the Industrial Revolution started in the late 1700s, humankind has burned fossil fuels that release carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Those gases trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere and raise worldwide temperatures. Today’s global greenhouse gas emissions mostly come from electricity and heat production (34%), industry (24%) and land uses like agriculture and deforestation (22%), according to the 2022 IPCC report. There’s 50% more carbon dioxide in today’s atmosphere than there has been any time in the last 2.5 million years.

Nowhere are the effects as noticeable as in Greenland, where temperatures are rising at least twice as fast as the rest of the world. They accelerate the ice sheet’s melting faster than it can be replenished by snowfall. Now, the island loses 234 billion tons of ice annually — seven times faster than three decades ago. Between 1992 and 2018, Greenland’s ice sheet has lost 3.8 trillion tons of ice, according to a 2019 NASA study.

With no change in emissions outputs, by the end of this century, global temperatures are projected to be at least 5 degrees warmer than the 1901-1960 average — possibly as much as 10.2 degrees warmer, according to the 2017 U.S. Climate Science Special Report.

Over time, these processes will change the coastlines for at least 140 nations and thousands of cities. The University of Chicago’s Climate Impact Lab estimates that by 2100, rising sea levels could prompt as much as $2.9 trillion to $3.4 trillion in costs per year globally as oceans encroach on coastal properties, assets and infrastructure. More than 200 million people could be displaced in that timeline, states a 2019 report by Climate Central.

The exact magnitude and timing of future sea level rise is still up in the air. Glacial melting is governed by a complex web of variables — some of which we don’t fully understand, like the influence of meltwater or the uncertainty of future global emissions. But some evidence is already in front of us, as the global average sea level has risen 8 to 9 inches since 1880. The rate of rise has doubled since the 20th century.

“Even a few feet of sea level rise would be disastrous for the planet’s coastal communities,” Englander says. “As the planet warms, the ice sheets melt and sea level rises, we have to understand, plan and adapt for a world which we’ve never seen in 6,000 years of civilization.”

Northern Exposure: Explore more images and accounts from Brittney J. Miller’s on-the-ground reporting for “When Ice Melts” at floridatrend.com/Greenland.