On an early morning flight in July, I awoke from a restless sleep. The flight attendant was asking passengers to prepare for arrival. As my eyes adjusted to the brightness, I squinted through the plane’s windows. Clouds painted the ground.

I blinked. No, not clouds — ice. As I slept, we had flown from Reykjavík, the capital of Iceland, toward Greenland’s west coast. The plane’s shadow was now stretched against the white surface of the massive ice sheet that coats about 80% of the island.

My bleary eyes widened, as I comprehended what I was seeing. I had read about it in The Ice at the End of the World, a 2019 nonfiction novel by the talented Jon Gertner all about Greenland. From his detailed reporting, I knew that the ice sheet stretched more than 2 miles deep at some points, that it was centrally domed from millennia of inland snowfall, that hundreds of glaciers now carry its ice toward the seas in every direction. But it was entirely different to see in person.

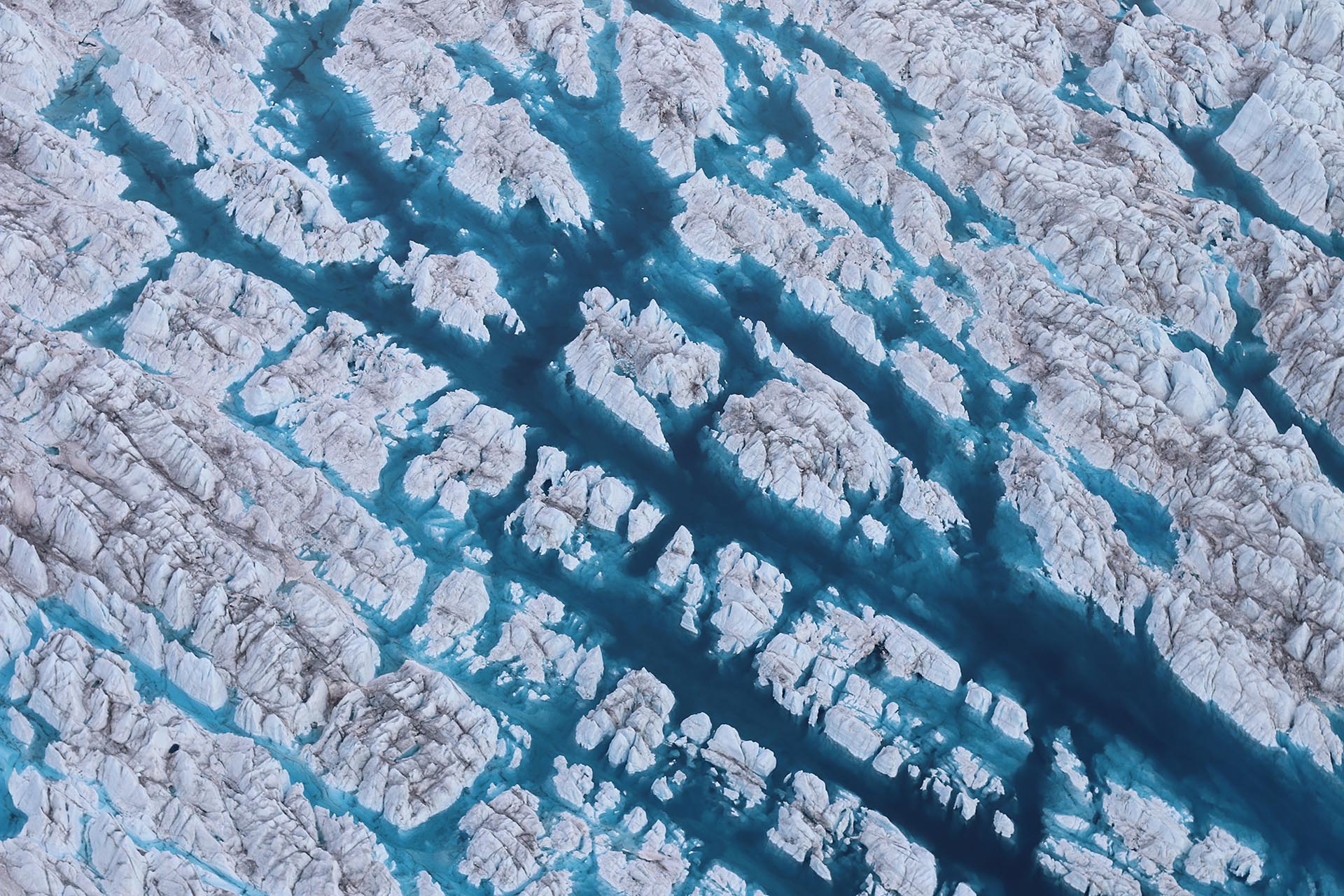

As our plane descended, I watched as the blank, bleak surface became patterned with cracks — some of which I knew were deep and deadly crevasses that have claimed the lives of many early explorers, some still harboring bodies in their frozen clutches. Then, the ice sheet ended in a dramatic cliff against a sea speckled with icebergs. A bright blue lined where the floating ice chunks met the water, promising a hidden half under the surface.

That first glimpse of Greenland was the first of many pinch-me moments I experienced during my week reporting on the Rising Seas Institute. The nonprofit’s leaders had brought visitors to the island for more than a decade before it merged with Nova Southeastern University earlier this year. The Fort Lauderdale-based school had invited Florida Trend onto its inaugural Greenland expedition and offered to cover some of the traveling costs. I was grateful to be able to attend, especially given my background in environmental journalism.

The trip to the top of the world was nothing short of otherworldly. From my hotel room window, I could spot icebergs drifting into the bay from a local icefjord. Every meal offered a bite of something new from the local cuisine — from ptarmigan to musk ox to whale to halibut. Most importantly, I learned about ice and glaciers from every angle: hovering above them in a helicopter, drifting nearby in a boat, browsing exhibits at the local Icefjord Center, even hiking on their crunchy surfaces. And I bore physical witness to their slow-moving but extraordinary journeys to the seas, where they contribute to global sea level rise.

It’s one thing to learn about sea level rise, as our group did in several educational briefings with the Rising Seas Institute throughout the trip. But to sit in the 200-foot shadow of a glacier, surrounded by the echoes of its slow disintegration via ice calving, is another thing entirely. To watch cerulean rivers of meltwater carve into the masses is a beautiful, scary and irreplicable sight. To simply touch the cold, crumbling icy surface felt like a lifelong goal for an environmental journalist. Walking on the Saqqarliup Glacier brought me to tears. It was the richest field reporting I’ve ever participated in.

You might wonder why a trip to Greenland is a Florida business story. It may feel extraneous to talk about a far-off icy land when you’re drowning in Florida heat. But never has Greenland’s fate been so intertwined with our state’s future, as members of the July expedition emphasized. Our coastal vulnerability grows with every drop of water melting from the island’s ice sheet, a torrent that’s growing as Earth warms with climate change. Florida’s fringes are coated with some of our most lucrative business hubs — take Miami or Tampa — and millions of residents whose futures will be shaped by projected sea level rise. It’s a geological story as old as time. (Literally, sea level rise has dropped and risen cyclically for millennia.) I saw it playing out before my eyes.

That’s why the resulting piece, “When Ice Melts,” is a business story. It’s an infrastructure story, a real estate story, an investment story. It’s an article that follows NSU, one of Florida’s 12 state universities, and its investments into sea level rise research and communication. It’s a tale of fear and hope, caution and proactiveness, science and controversy. Most of all, it serves to inform Florida Trend’s audience about our state’s business future and what may threaten it.

Do you have a national or international opportunity you’re proud of, one that’s helping elevate Florida in the business world? Let Florida Trend know. I may just find myself, bleary-eyed but buzzing, on another plane in search of the next big story.