A-Lotto Money

Posted 10/3/2013

On a muggy Wednesday morning in early June, 84-year-old Gloria MacKenzie and her son Scott left his home in Jacksonville's working-class Lakeshore neighborhood in a silver Ford Focus and drove 160 miles west on Interstate 10.

They parked in a lot at the headquarters of the Florida Lottery in Tallahassee, where they were joined by a phalanx of advisers. Wearing sunglasses and a pink short-sleeved sweater, MacKenzie walked into the building and told the clerk at the front desk that she was there to validate a ticket.

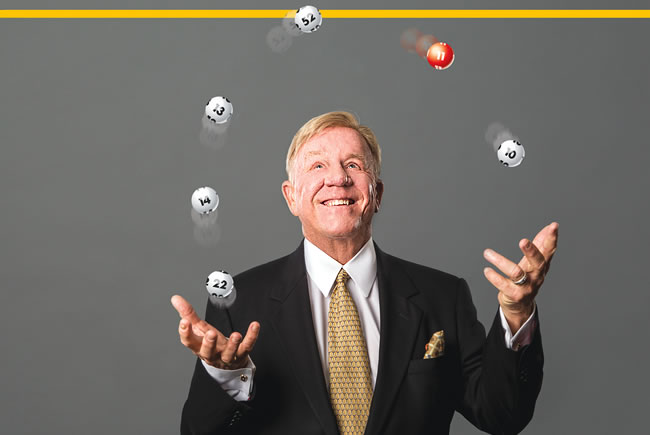

The office went abuzz when they learned which ticket it was — the single winning ticket for the $590.5 million Powerball lottery, which MacKenzie had purchased 17 days earlier at a Publix in Zephyrhills. The numbers 10, 13, 14, 22, 52 and a

Powerball of 11 made her and her son the biggest single winners of a lottery in U.S. history.

The MacKenzies filled out the necessary paperwork and left a few hours later, answering none of the questions lobbed at them by the reporters who had gathered in the lobby. Their only comment came via a prepared statement, read by a lottery executive, in which Mac-Kenzie called the winning ticket a blessing and pleaded for privacy.

Among the horde of advisers, visible in photos and video images of the day, was a sandy-haired man in a suit who helped usher MacKenzie and her son out of the building.

The man is Harry "Hank" Madden, financial adviser to the MacKenzies and CEO of Madden Advisory Services.

Madden, 69, born and raised in Jacksonville, is a Vietnam veteran who has worked as a financial planner since 1975. For nearly 20 years, he has co-hosted a popular weekly radio program on WOKV-104.5 FM called "Smart Money." Scott MacKenzie had heard the program and called Madden after he learned his mother had the winning Powerball ticket.

Madden, who describes his firm as "Christian-based," sees divine intervention at work, but he wasn't sure at first he even wanted to accept the blessing. He'd worked with lottery winners before, he says, "but nothing of this magnitude."

He knew immediately that the size of the MacKenzies' portfolio — $270 million after taxes — and complex planning needs would drastically change his work life, starting by instantly doubling the assets under Madden's management. "A case of this size will require every bit of your expertise and some you didn't know you had," he says.

Madden says he knew that helping the MacKenzies invest their riches would be the easy part of his job. First on his agenda was protecting their identities — and personal security. At the same time, Madden connected the MacKenzies with William Brant, an attorney in Jacksonville who had worked with lottery winners before and was familiar with security firms that can protect wealthy families.

MacKenzie immediately moved from her modest apartment in Zephyrhills to her son's home in Jacksonville. "We had them sequestered," Madden says. "Initially you have to get them out of where they currently live." They got new email addresses and phone numbers. He also set up corporate names for them at private clubs where they could escape public scrutiny. Madden and Brant advised them to purchase a kidnapping insurance policy. "No matter how careful you are with clients of this size, you will get bombarded with people trying to get in to see them and write them," Brant says.

Before the MacKenzies validated the ticket, Madden urged them to set up blind trusts in order to avoid their names being leaked. He also had to worry about the tax penalties for "gifts" because the IRS will want proof that MacKenzie and her son had arranged to share the prize in advance. "We made sure to go back and check telephone logs," he says. "If you are off, the IRS can say, no you didn't have a pre-arranged deal. What you did is make a gift" and MacKenzie would face a 40% gift tax. Madden's team developed a sworn affidavit to head off the IRS.

Madden also helped the MacKenzies assemble a financial team, locating accounting firms capable of handling the complexities of this case, though the MacKenzies have the final say over any hires.

Preserving capital

Because the lottery prize is so large, Madden says, his focus is on preserving the wealth rather than growing it, making sure that it is sustained over a long period of time to share with children and grandchildren. That involves setting up dynasty trusts, which minimize estate taxes. The assets in the trust make distributions to each generation, and the entire trust isn't subject to estate taxes. "It's not only the lives of a couple of people now, but who knows how many lives in the future," he says.

At Brant and Madden's urging, the MacKenzies are setting up trusts designed just for charitable giving, which also ease the tax burden. The New York Daily News reported that MacKenzie committed $2 million to fix the roof at a high school in Maine where her daughter is a teacher.

Madden won't disclose details about how they plan to divvy up the prize money but says there will be "different trusts" that are "substantial in nature."

The size of the MacKenzies' winnings means they're unlikely to blow through their money in a few years. Madden told them with $270 million they could "drive down Ponte Vedra Boulevard, which is a very exclusive area, and buy any home they wanted to, add a 10-car garage, buy 10 exotic automobiles and never touch the income for one year. You're dealing with wealth at an entirely different level."

The MacKenzies may have taken Madden's observations literally. Several newspapers reported that MacKenzie bought a Jacksonville home in the Glen Kernan Country Club community for $1.175 million. The deed to the home was transferred to Melinda MacKenzie, one of MacKenzie's daughters.

A new mindset

Madden says the challenge for any lottery winner is getting over the psychological shock and adjusting to the identity of a wealthy person. Most people buy tickets on a whim, he says, not taking time to seriously think about what they would do if they were millionaires.

"Picture somebody making $25,000 a year and living in a $45,000 house," he says. "Now they are worth $140 million. It's hard to begin to conceptualize the difference between the two."

Meanwhile, the demands of Madden's new client have meant he's had to hire more people to add to his six-person firm. He also had to take additional security precautions, upgrading the security and software systems at his firm. "We've already had intrusions," he says, describing emails designed to glean information about the MacKenzies that he referred to the FBI. "They are after this money."

Madden also hired Brant as his firm's attorney to ensure client-attorney confidentiality protections. And he also reassured his existing clients that he remains focused on their accounts. "They were all very happy for us and thrilled for the firm," he says.

Madden is a "fee-only" financial adviser, meaning he is paid an agreed-upon fee for his services rather than a commission for securities bought and sold on behalf of the client. Madden says he negotiated a fee with the MacKenzies, which he would not disclose. The MacKenzies "wish to have everything as private and personal as possible," he says.

But fee-only financial adviser Susan Spraker, CEO of Maitland-based Spraker Wealth Management, says she charges 0.5% for assets over $2 million. For an estate worth $270 million, that amounts to an annual fee of $1.3 million. Spraker says Madden probably worked out an arrangement for a fee of less than $1 million. "To have a client agree to have that much wealth managed, a special arrangement was probably made," she says.

Brant says he went to high school with Madden and has co-hosted money management shows with him. Madden has an ability to put clients at ease, he says. "Hank is really good at what he does and is good at building client trust and knowing how to diversify and not do crazy things," Brant says.

Madden says the MacKenzies' decision to trust him with such a staggering sum of money was "one of the most humbling experiences I have ever had," he says. "It is a responsibility I do not take lightly."

Taking His Own Advice

Long before he became a financial adviser, David Rush was a network correspondent for NBC News. Over his career, he covered parts of three presidential administrations and financial affairs and co-produced a radio documentary on lottery winners.

"One lady won a million bucks," Rush says. "So she bought a $2-million house." She also purchased an expensive Cadillac, he says. "The first thing she did was not make the payments, and she went bankrupt."

Rush says that convinced him that "if I ever win the lottery, I know exactly what I am going to do." After leaving NBC News in 1987, he become a financial adviser in Naples.

Over the years, he advised four lottery winner clients, and in 2002, he got the chance to follow his own advice, winning $14 million as part of a $104.5-million lottery jackpot.

"It was quite a shock," Rush says, speaking from his summer home in North Carolina. "I started hearing from people we hadn't heard from in years, congratulating us, or from local people who wanted us to donate to their cause." He was inundated with letters. "I got 1,500 letters asking for money and 102 marriage proposals. I finally stopped taking any mail if it wasn't from somebody I knew," Rush says. He even had one stalker, he says.

Despite the distractions, Rush was able to stick to the plan he had formulated more than 20 years before, which revolved around "church, charity and children and grandchildren."

At 71, he was already planning to retire soon and did the following year. He set up college funds for grandchildren and great-grandchildren and gave his own children their inheritance early. "We gave 85% of it away originally," he says, to family and also to "food programs, housing programs and some people we knew casually who got into financial problems. They didn't ask us for money. We gave it to them." That left him with $2 million, which he wound up giving away within five years.

"I was better prepared than most because I was a financial adviser," says Rush, now 82.

His life isn't much different now than it would have been without the lottery, he says. "It enabled us to retire a little more comfortably," Rush acknowledges.

The main difference, he says, was that now he was branded a "lottery winner" and became the subject of gossip and incorrect assumptions among neighbors in his close-knit community of Marco Island, which is just south of Naples. "People are funny about money," Rush says.