Kay Jackson, a member of the city council for small town Cape Canaveral, wants to be crystal clear about how she and the city feel about the industry centered on the launch pads on Merritt Island across the port inlet.

“We love our space,” Jackson says. The city seal, after all, reads “Sun Space and Sea.” That said, she hears from residents about how their windows shake during the launches. She has cracks around her condo door. “We’re fans of the space industry,” she says, “We’re supportive of them but we have to be realistic.”

Florida launches numbered a record 109 in 2025, 101 of them from Elon Musk’s Space Exploration Technologies, SpaceX.

A dose of realism and a test of that love comes this year. Demand for space transportation, a rare Florida heavy industry, is set to make the world’s busiest spaceport even busier. Florida launches numbered a record 109 in 2025, 101 of them from Elon Musk’s Space Exploration Technologies, SpaceX.

Planners anticipate more this year. Most will be satellite-deploying milk runs by SpaceX and its Falcon 9 rocket. But this year also is scheduled to see the second launch of NASA’s towering “Space Launch System” on which America’s return to the Moon depends. Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin wants to fire its New Glenn rocket off more rapidly and build a bigger one. In November, it announced a new configuration that will make it taller than the Saturn V that put Apollo on the Moon and that will rival the Space Launch System in power. Then there’s SpaceX and its desire to launch, up to 120 times a year, its Starship — the most powerful launch vehicle ever built. The launch tower SpaceX has under development at Kennedy Space Center itself dwarfs the other launch pads.

Apollo’s Saturn V launched 13 times over seven years. SpaceX and Blue Origin plans call for launching that many giants in a month. Jackson’s constituents and the rest of Brevard County better batten down the bric-a-brac.

A BOOMING SECTOR

Beyond Bezos, Musk and the Moon shot, smaller operators have their own launch plans. Military demand looks to grow, especially if President Donald Trump’s Golden Dome satellite-based defense shield takes off. Meanwhile, the AI hype machine now includes basing solar-panel-powered AI data center satellites in orbit. Space Florida, the state’s spaceport financing authority, surveyed launch operators in 2024 to come up with a projection of 282 launches and recoveries annually by 2033, rising to 571 in 2053 and 1,252 — more than three a day — by 2073.

Maybe. During the heady success of Apollo 11 in 1969, some NASA executives foresaw a human Moon colony by the 1980s and human Mars expeditions by 2000. Trump in his first term issued a directive charting America’s return to the moon with the Artemis program. Plans called for landing astronauts in 2024. Now, 2028 looks optimistic. Bezos’ delayed New Glenn is supposed to fly 12 times a year. It went twice in 2025. Musk’s Starship, as of the New Year, had launched 11 times from Texas but had not reached orbit. Space is brutal on development timetables.

But the payoff has promise. The space economy globally will reach $944 billion by 2033, up from $596 billion in 2024, driven by demand for satellite services from industries as diverse as agriculture and logistics in need of navigation, Earth observation and communication services, says Paris-based global space consulting firm Novaspace. Satellite broadband demand, a $320-billion market opportunity, will require the world to put an average of 3,700 satellites per day into space, or seven tons of satellites daily, over the next decade, Novaspace forecasts.

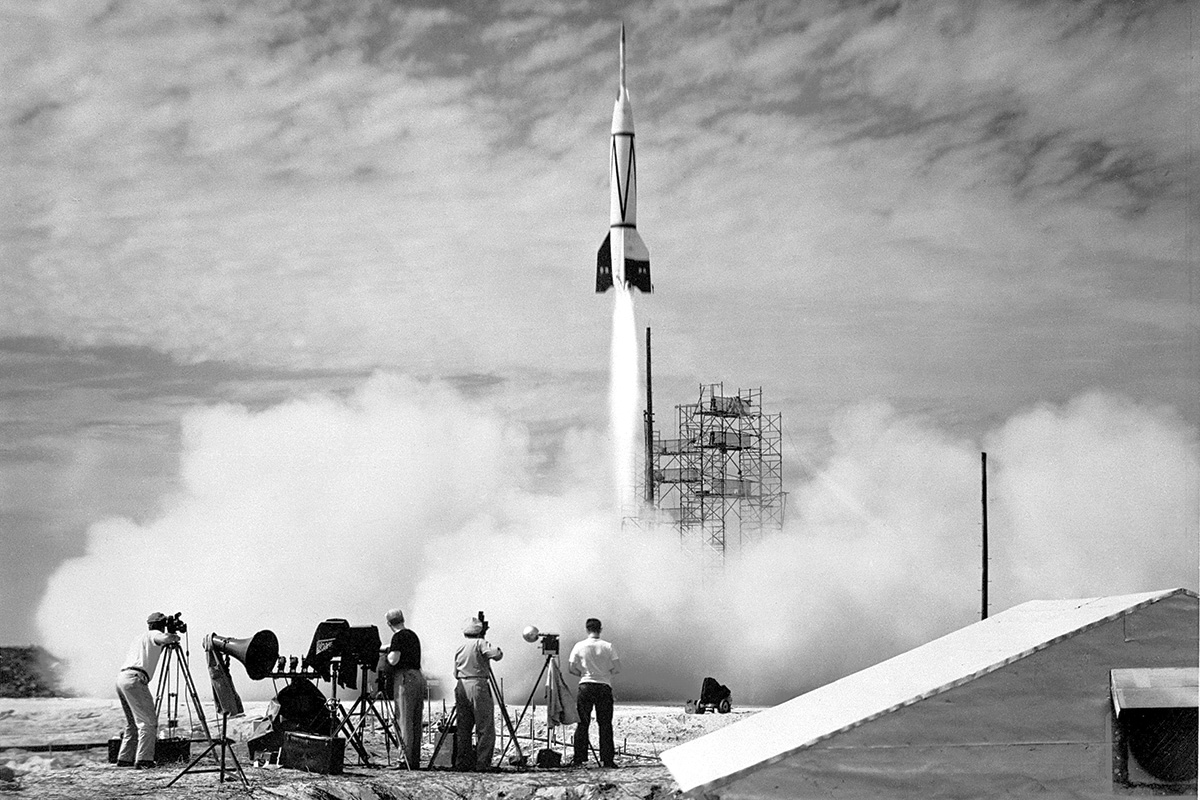

Much tonnage will rise from the spot the federal government picked nearly 76 years ago for rocket testing — in part because the area was remote and lightly populated. In 1950, when the first rocket launched from the Cape — Bumper 8, a combination of a captured German V2 and American-made technology — Brevard numbered 22,400 people. Today, it’s Florida’s 10th most populous county with more than 667,900 people.

The Cape’s natural advantage is that it provides access to sought-after orbits near the equator, offering broad coverage of the Earth for satellites, and the geostationary orbits coveted by defense, science and commercial players. The Atlantic supplies a safe place for launching east with the Earth’s rotation for added boost.

Through the decades, Kennedy Space Center and what’s now the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station had a big year if they reached double-digit launches. That would still be the case today, even in the current race between the United States and China for the orbital high ground and a return to the Moon.

What boosted launches to a record-breaking launch count — “cadence” is the industry buzzword — owes to the space private sector dominated by Musk’s SpaceX, founded in 2002. SpaceX, in the words of Space News’ SN Intelligence on the SpaceX economy, has gone “from scrappy startup to the space sector’s 800-pound gorilla.” SpaceX’s reliable, reusable — and therefore cheap — Falcon 9 rocket gave it a near monopoly in the launch business and gave its Starlink satellite broadband first-mover advantage in the market, a larger market than the launch business. “The pie is way bigger on the SATCOM market,” says Novaspace’s Lucas Pleney. Thanks to vertical integration — no launch middleman — Starlink accessed orbit at a fraction of rivals’ cost, he says.

Starlink’s 8,500 satellites and 8 million subscribers in 140 countries span residential, government, maritime and aviation markets. It’s now growing a direct-to- device business that could let Starlink be a mobile network operator — an AT&T, only global. SpaceX hit $11.8 billion in revenue in 2025 with the majority of revenue, for the first time, from Starlink.

BIG VIBRATIONS

Given SpaceX’s dominant position, the prospect of it repeating Falcon 9 reliability and regularity with a 10-times more powerful Starship has the industry wondering. With twice the thrust of the Space Launch System and at least 10 times the noise of a Falcon 9, Starship has Cape Canaveral Council member Jackson wondering too. “With Falcon, it’s not nearly what we will experience with Starship,” Jackson says.

SpaceX filed last year for federal approval to launch Starship up to 120 times a year from the company’s two pads at Kennedy and next door’s Space Force Station. Keep in mind that every launch is three aerial events: first, the launch itself. That’s followed several minutes later by a sonic boom and the flyback of the Starship’s Super Heavy booster to the pad. The third event is the return of Starship itself from space, crossing Central America, the Gulf and Florida from west to east, although it also could land on a drone ship or splash down in the Pacific or Indian oceans.

That’s potentially 360 times a year that parts of the waters off the Cape — home to the world’s busiest cruise port — will be closed, airspace restricted and Canaveral-area windows and china rattled. The FAA estimates night launches will wake 10% to 14% of people nearby. The sonic boom from the Super Heavy booster return will rouse 42% of residents — 82% of people in mobile homes and campers.

“It’s a little frightening to think about what the impacts could be,” Lilian Myers, a city resident and entrepreneur in residence at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, told the Cape Canaveral City Council in April. (The council, following proclamations for Arbor Day and pickleball, was debating a contract to monitor vibrations at a sampling of sites to establish a baseline before Starship launches commence.) “I think about it quite a lot and certainly as the years have gone by and the window rattling has gotten to be worse and the cracks in my ceiling have appeared and a crack that goes all the way from the base of our building to the fifth story that was repaired,” Myers said.

The line of the concerned has grown long, though nearly everyone prefaces their worries with an endorsement of the space industry and the jobs it brings. SpaceX and Blue Origin have invested billions in Florida facilities, whether Blue Origin’s “Rocket Park” or SpaceX’s Gigabay assembly building for joining Starship to its Super Heavy booster. Blue Origin says it employs nearly 4,000 people in Florida. The state is investing billions too — $1.2 billion at Port Canaveral, which needs to expand to handle the maritime needs of space companies. The state transportation department says it will spend $90.5 million this year on spaceports.

“We are not in any way against SpaceX doing science and bringing research,” says Erich Schuttauf, executive director of the Kissimmee-based American Association for Nude Recreation. The question, he says, is “What happens now that SpaceX becomes a bigger neighbor?”

A lengthy list of nudists and their groups filed concerns with the FAA. Schuttauf says the association can live with the FAA-estimated closing of Canaveral National Seashore’s Playalinda Beach for 44 to 60 days a year — almost two months a year — and Apollo Beach. Those clothing-optional beaches provide “family-friendly nude recreation in a wholesome environment,” he says. The group wants to be sure the public gets plenty of notice. “No one wants to drive three hours to go to the beach and then find out it is closed today,” Schuttauf says.

AIRSPACE COMPETITION

Environmentalists, the fishing industry and, in particular, the airline industry have their own issues. Air passenger travel to Florida, the only state with four large hub airports, is increasing as it is. Orlando is the eighth-busiest airport and Miami the 10th by passenger volume. A dozen Florida locations are among the top 100 most-delayed nationally.

Airlines for America, a group representing U.S. passenger and cargo carriers, says Cape launches already mean ground stops, lengthy re-routing around no-fly zones and higher fuel costs. The industry says launches force flights to be moved from routes over the Atlantic to over the peninsula; the resulting congestion leads the FAA to restrict traffic for safety. The Jacksonville and Miami air route centers — which manage air traffic between cities — already were second and third in delays in 2025 behind New York Center. Jacksonville Center’s delay rate is 20 times worse than in 2010 and Miami’s has increased 10-fold, the group says. Launch-caused effects take days for the nation’s airspace system to work out, the group says.

The Airports Council estimates SpaceX’s Starship will cause up to 2.3 million passengers to experience between 600,000 to 3.2 million hours of air travel delays.

The FAA estimates each Starship launch will add 40 minutes to two hours of delays for airplanes and affect up to 400 aircraft at peak travel and, for Starship re-entries, up to 600 aircraft at peak travel. Closure areas can span 1,600 nautical miles. Various trajectories run from Canadian airspace to the Bahamas. The January 2025 loss of a Starship launched from Texas shut air space for 90 minutes, diverted 20 flights and delayed 243.

The Airports Council, a different group, estimates Starship will mean 900,000 to 2.3 million passengers will experience 600,000 to 3.2 million hours of delay at a cost of $80 million to $350 million annually.

“The FAA has got to find a way for both commercial aviation and space launches to cohabitate and coexist without impacting commercial traffic. Let me caveat this by saying we have no issue whatsoever with what SpaceX is looking to do,” says Tampa International Airport Chief Operating Officer John Tiliacos. “I think it’s great that we’re pursuing space and we’re further exploring that frontier. I’d love to be on a rocket, but as someone that has responsibility for the efficient running of an airport, I’ve got to raise a flag to say, ‘Hey, I like this. I think it’s cool. How do we both coexist?’ It’s going to get to a point where they’re going to want to launch all day long, 24 hours a day, and that can have profound impacts on the National Airspace System. The folks that are not going to be very happy are the traveling public.”

SHAKE, RATTLE AND ROLL

SpaceX, in an online post, says Falcon 9s average flights every two days with “minimal impact on air traffic” and “little-to-no negative” effects on fishing, shipping or air travel thanks to its research into finding the right size for closure areas. Already since 2022, the hazard areas for Falcon 9 Starlink launches have been cut by 66%, SpaceX says. It added that it’s confident Starship won’t disrupt other launch operators. It wants “airport-like operations” at the Cape with launch providers operating as seamlessly as airlines taking turns using a runway. “SpaceX is committed to working collaboratively with federal regulators, the federal ranges and industry partners,” it said. “Presently, there is unprecedented demand for access to space,” it also has said.

Indeed, Bezos’ Blue Origin wants to ramp up flights of its New Glenn, a made-in-Florida rocket, to build out its Amazon Leo satellite rival to Starlink. Under CEO Dave Limp, brought in from Amazon, Blue Origin is shifting from R&D to manufacturer and operator. Blue Origin has its eyes on the mega-satellite system market, missions to the Moon and Mars and national security launches such as for Golden Dome. NASA last year floated re-opening the bidding process for making Moon landers for the early Artemis missions, originally won by SpaceX, to Blue Origin and others. Blue Origin’s lunar factory at the Cape is for building a fleet of lunar landers.

A growing launch pace by all benefits the United States and its space ambitions, but too much could cause difficulty, Novaspace’s Pleney says. “If you increase launch cadences, where you have a Starship flying almost every day, you could rapidly see some impacts that are not sustainable, whether it is for the people living around it, or for the fauna or even for the structures of the buildings around,” he says.

Council Member Jackson, who has studied effects on Texas towns, says the city of Cape Canaveral needs to watch out for its citizens and infrastructure. When interviewed, she had just a few days before watched New Glenn’s November flight. The thrilling sight reminded her of another: The return of a Falcon 9 booster to the launch pad on the Cape, with the sonic boom rolling down the beach to where she stood.

“I can’t tell you how excited I felt, personally, watching Falcon 9 land back the first time,” she says. “It’s concerning, though, when you feel the vibration.”

Launches by the Thousand

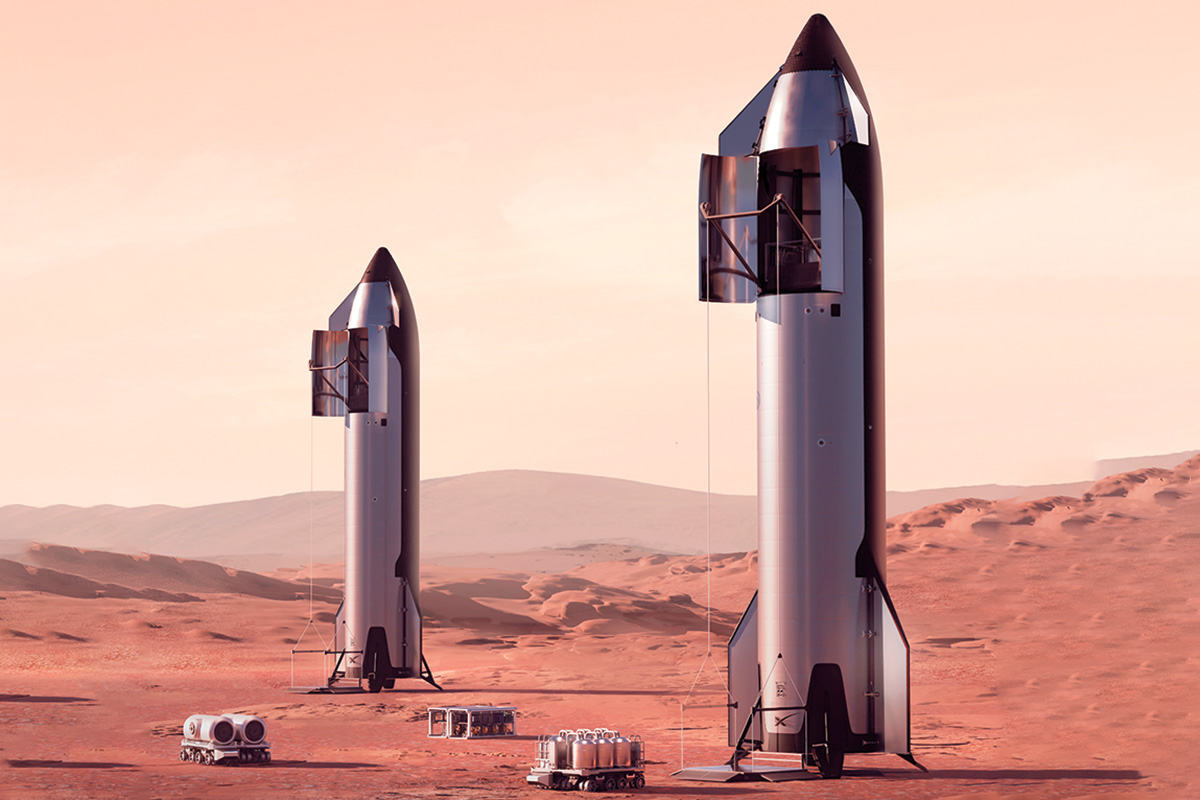

Elon Musk spitballs that building a self-sustaining Martian city requires 100,000 people and 1 million tons of cargo. That much cargo alone would take 5,000 flights of his Starship. But Starships consume their fuel just reaching orbit with cargo. Convenience stores being scarce in Earth orbit, Mars-bound spacecraft would have to fill ‘er up from tanker spacecraft that themselves would take 10 to a dozen Starships to top off. That’s 50,000 to 60,000 Starship launches just for fuel. “It’s absolutely enormous,” says Lucas Pleney, manager of the Paris-based global space consulting firm Novaspace.

Another way to think of it: Musk will have to turn out rockets faster than Boeing and Airbus build planes. The trouble with dismissing such an outlandish project: Twenty years ago, observers dismissed Musk’s vision of a private company providing low-cost space transport with reusable rocket boosters. Late last year, SpaceX reached 500 flights with reused rockets.

More If By Sea

A few entrepreneurs look to the sea to alleviate the pressure on Florida’s increasingly busy launch sites and a scarcity of coastal locations who want heavy industry on the beach.

“Demand for launch pads is starting to exceed supply. Demand for launch pads in Florida definitely exceeds supply. You’re not going to build another Cape Canaveral very easily,” says Tom Marotta, CEO and co-founder of the Virginia-based Spaceport Company, which has an office on Merritt Island. To date, it’s launched missiles five times — nothing to orbit — in the Gulf from its Mississippi-based ship. He hopes in the spring to launch a rocket to 100,000 feet for the Air Force. He says the company is profitable.

St. Petersburg-based Seagate Space and its cofounders Michael Anderson and Sean Fortener are developing a sea-based launch platform and hope to do a demo of a sea launch in 2027. The two formerly were with Jacksonville-based maritime company Crowley.

There’s precedent for sea launches. In the 1990s, interests from several countries created a sea-launch company that had successful launches before failing as an enterprise. SpaceX a few years ago acquired oil rigs for sea-based launches but later sold them and abandoned the effort. China, with spaceport issues of its own, has launched rockets more than a dozen times from floating platforms. “They are scaling,” Anderson says. An advantage of sea launches: The rocket can be floated closer to the equator to get more of a fuel-saving boost. “We want to be the maritime partner for the space industry, working with them on launch and recovery. We believe we can offer them a more optimal solution,” Anderson says.

Nationally, there are 14 licensed spaceports, but flights to orbit have come from just four locations: Florida, Wallops Island, Va., Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, and Alaska.