Celebration: The Inside Story

In early January 1987, I was in Tallahassee, finishing my last weeks as secretary of the Florida Department of Community Affairs, the agency that helped pass and implement Florida’s historic 1985-86 growth management legislation. I got a call from Peter Rummell, then president of Disney Development Co., Disney’s real estate arm. Peter was in Paris, negotiating the deal that would allow Disney to begin development of EuroDisneyland (now known as Disneyland Paris).

Peter didn’t need my help with the French project. He was calling in part because Disney’s new executive leaders — Chairman Michael D. Eisner and President Frank Wells — were about to launch a major expansion of Walt Disney World, including a third theme park, thousands of hotel rooms and associated back-of-house space. Disney would need help in complying with Florida’s new state growth management laws — I had helped pass them and had overseen development of the rules Disney would have to follow.

But what Peter really wanted was to see if I was interested in helping the company take on “the most significant, complicated damn planning assignment you’ve ever faced,” as he put it. Peter wanted Disney — international theme park and resort operator, moviemaker and media conglomerate — to consider taking a giant step outside its core business to develop a residential property on Walt Disney World property.

The idea of a Disney residential project had been discussed two years previously at a tightly managed, internal symposium involving Disney’s top leaders and some of the nation’s top visionaries, futurists, planners and developers. But no consensus had emerged — either on what kind of development Disney should undertake or whether the company should undertake a residential project at all.

One participant, for example, had suggested that a community “built around a canal system would be extraordinarily exciting,” but another asked, “Do you really want full-time citizens” inside Disney’s grounds. A residential development “may be the ideal community and it may be unique in terms of design, but is it moving Disney out of its business?” one participant asked.

The conference hadn’t generated a plan, but it had elevated the discussion of the subject to the highest levels within the company. The month before our call, Peter had written a closely held memo “Residential Development at Walt Disney World.” The memo identified the keys to success … “the software will be more important than the hardware … the biggest issue is we have no beach – we have to create a beach that will attract consumers who seek out Florida.”

The memo, and his call to me, were the initial steps in putting together what became Disney Development Co. — an all-star team of commercial, hotel and residential real estate development professionals that would report directly to Michael and Frank. No such entity existed anywhere in the Disney at that time.

In February 1987 I joined Disney Development as director of residential development and began to evaluate 8,000 acres on the southernmost edge of the 27,000-acre Central Florida property that Walt Disney had assembled in the 1960s. We engaged Robert Charles Lesser to do a market analysis and recommend a residential program. Michael selected four architect-planners to provide master plan schemes based on the Lesser program.

At that point, the project was called Osceola Mixed Use Development — sometimes called OMUD, sometimes OMD, sometimes MXD. By mid-summer 1987, planning was underway. I had occasional visits or calls with the consultants, but they were mostly on their own — each earning $25,000 honoraria for their trouble.

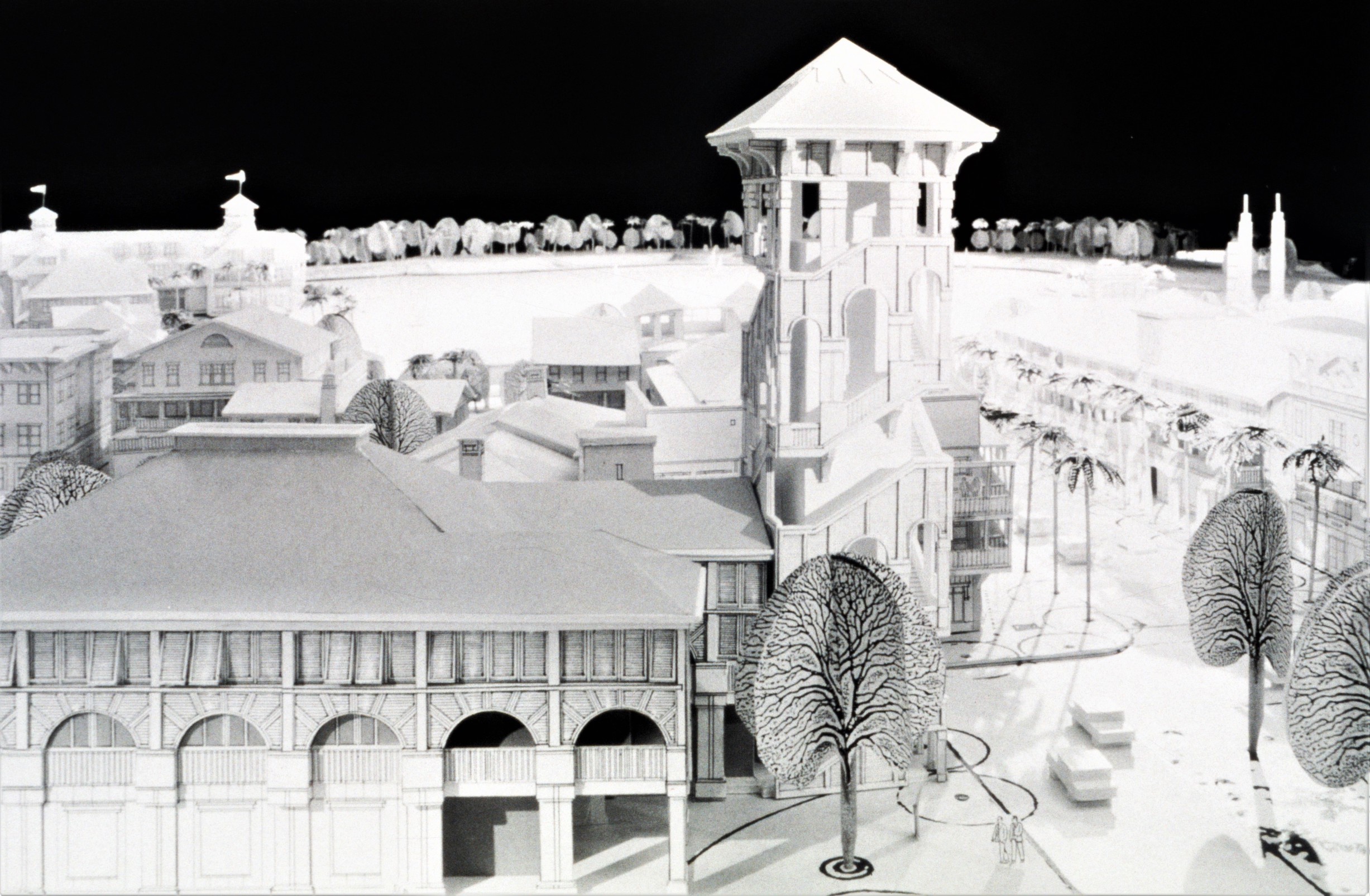

The four OMUD master plans were presented to Michael and Frank in the fall. As anticipated, three architects proposed grid-street schemes based on New Urbanism/Traditional Neighborhood Development concepts, with houses close to streets, rear alleys for garages and services, a mixture of housing types and a multi-use town center. The fourth was a typical post-World War II suburban plan with winding roadways, cul-de-sacs, no defined town center and all garages facing the streets.

Michael favored the New Urbanist-flavored proposals advanced by three architects: Andres Duany (Duany/Plater-Zyberk), Bob Stern (Robert AM Stern Associates) and Charlie Gwathmey and Bob Siegel (Gwathmey-Siegel). He liked parts of what all three were suggesting and directed us to produce one consensus plan. As we left the meeting, I told Peter this would be “worse than forcing Ford, Chrysler and General Motors to build one car!”

Between November 1987 and January 1988, I spent a lot of time in meetings at Gwathmey-Siegel’s offices in New York. As an architect myself, it was a unique experience getting an inside look at three of the biggest, most successful egos in our “profession of egos.”

Andres was a forceful advocate for his plan’s principles. Bob had the biggest ego. Charlie Gwathmey, Paul Whalen of the Stern firm, and I helped as mediators. The participants weren’t afraid to raise their voices, but things usually calmed down by mid-afternoon, when Team Andres served Cuban coffee every day. In time, a consensus plan emerged with no one injured and egos mostly intact.

Disney Development believed we should test the plan using Focus-groups selected out of the Parks, before presenting it to Michael. Among the many things I learned about Disney was that it does more consumer polling, surveying and testing than anyone I’ve ever heard of. We engaged the Decision Research Corporation to conduct 12 focus groups, with participants recruited from among the visitors to EPCOT. The sampling included various categories of potential consumers — Chicago Seniors, New York/New Jersey Seniors, Entry-Level Orlando Residents, Disney Cast Members and Residents of Sun City (a 55-plus active adult development near Tampa). We tested both the consensus plan (Plan T), as well as a more resort-oriented plan from Ed Stone (Plan R).

The major conclusions from the research were:

• There was huge interest in a community in which Disney was involved, but the name Disney should not appear in the name of the community.

• Disney’s involvement added substantial value but also created huge expectations that were likely unmeetable in a residential development.

• About two-thirds of the focus-group participants liked the resort-oriented plan, with a third favoring the consensus plan.

We presented the results of the focus groups and the Consensus Master Plan 2 to Michael and Frank in mid-1988.

Meanwhile, however, Michael had some ideas of his own. One was a concept for what he called The Institute, a hands-on summer vacation-educational experience modeled after Chautauqua in upstate New York, which he had often visited while growing up. He also had an idea for The Workplace, a theme-park type experience in which visitors could experience how products are designed and manufactured. The idea was similar to how visitors to Hershey’s chocolate factory in Pennsylvania get to “walk through” Hershey’s manufacturing process — but done the Disney Way. In addition, the Disney Development team was proposing a major regional mall be added to the OMUD Project, west of I-4.

Complicating things further, Michael and Frank had begun regularly to question whether the company should get involved in a residential project at all. “We are not in the community development business … that’s why we sold Arvida! How do you know we have enough land to build out WDW?” they asked.

To me, however, the best option for the 8,000 southern acres was clear: Residential development. Just holding onto the land would make it exponentially more difficult to develop at some future time. Selling the land didn’t make sense because Disney would put so many land use restrictions on it — so a future owner wouldn’t build something that competed with Disney — that the limitations would have wiped out most of its value.

A final complication involved transportation. Florida’s Turnpike, an FDOT entity, was considering connecting I-4 to Orlando International Airport, and Disney didn’t at all like the proposed route, which intersected the existing EPCOT interchange. We were pushing for it to instead come through the OMUD property, meaning a multi-lane toll toad would slice through the project. This change got Osceola County involved, as well as several other landowners – producing more complications to deal with.

All those issues affected what became known as Consensus Master Plan 2. Michael also wanted a new team of architects and planners to look at it. So we turned over the first two master plans, along with all the notes and feedback, to Jacque Robertson (Cooper-Robertson) and Marilyn Taylor and David Childs of Skidmore, Owens & Merrill (SOM). As this third stage of planning proceeded, Disney Development began design competitions for The Institute and Regional Mall.

Disney’s Executive Vice President of Strategic Planning Larry Murphy and his team were responsible for answering the Michael/Frank questions about how much land Disney needed. They also vigorously sliced and diced my data on the residential project. I never believed Larry was necessarily a fan of OMUD, but he was one of the most interesting characters I met in my 18 years at Disney. With a nickname for everyone (I was “Big Lew”, Jay Rasulo who started as an analyst and rose to the top of Disney leadership was “Jaybird”), Larry and his band of financial and strategic analysts typically would arrive at midnight from California and swoop in, ready to work.

Ultimately, Larry and his team evaluated Disney’s 27,000 acres along with environmental permitting requirements and transportation capacity needs under the new growth management laws. The critical question was how much land was needed to build out Disney. The calculations were fascinating, the logic simple: Project how many millions of guests per day and visits per guest in days would come to Florida, what share of that number Orlando would capture, and what share of Orlando’s portion Disney would capture.

The Florida capture of 8.2 days remained consistent throughout the analysis. The Orlando share grew from a then-current 5.2 days to 6.7 days. The biggest change was the Disney capture – it grew from 2.7 to a projected 4.5 days. Once you have the projected number of individuals, it’s multiplied by the number of days, and you get total number of guests – for instance 13 million guests times average stay of 4.5 days equals 60,000,000 total annual attendance.

The total annual attendance figure drove every other decision — how many theme parks, hotel rooms, other recreational facilities, back-of-house space, etc., would be needed, and how much acreage would be required to accommodate them.

In February 1989 came a pivotal meeting between Larry Murphy, Disney Development Company, Michael and Frank. Key discussion points were how the transportation improvements so critical to the build-out of Walt Disney World were politically, fiscally and financially linked to OMUD. Osceola County’s support of the project depended on successful development of its major east-west toll road, Osceola Parkway, which depended on WDW traffic, which Disney needed, and was critical to gain approval of both of the two new I-4 interchanges.

Michael and Frank directed me to proceed to finalize the agreements on the transportation improvements and get approval of the two new interchanges. They acknowledged that future theme parks — “gates,” the company calls them — would be built north of U.S. 192.

And they approved proceeding with OMUD, with several conditions, including the development had to be high quality, Arvida-style. Michael wanted Disney to stop at 192, but did not support selling the OMUD land, envisioning it as “a good transition between Disney and the rest of the world.”

What drove the decision to proceed? Some have speculated that Disney was trying fulfill Walt’s original dream of an Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT), but WDW leadership was very insistent that OMUD not appear as “the real EPCOT … because the real EPCOT had already been built.” Others saw a financial motive. The financials presented in the February 1989 meeting did project some positive net present value for OMUD – but not near as much as one good movie, with almost no effect on earnings per share. The reason wasn’t financial.

I believe it came down to the sensibilities of Michael, who became engulfed in the design progress of OMUD, and Frank, who focused on the land, environmental and transportation analyses. Michael in particular had such huge creative mental energy, and a wonderful taste, sense of balance and scale, and other attributes an architect must have. I always felt he was a “frustrated architect” – but a fine one!

In the wake of the February 1989 meeting, a third master plan was starting to coalesce, and the design competitions for The Institute and regional mall were nearing completion. Late that year, Peter authored another of his comprehensive thoughts about the project. Titled “The American Town - a living laboratory in the sense it will be experimental in many respects, from the way residents are provided public services, to the infrastructure that serves it. (W)e will also develop some ideas that will be copied in many places for years to come. And it will be developed carefully enough that it will become a model for new town development everywhere.”

Early in 1990, Michael decided that Jacque Robertson and Bob Stern should produce the final master plan. I welcomed this as we were under a lot of pressure from Osceola County to announce the project. That meant, of course, that we needed a real name for it – Disney was not going to announce something called OMUD.

I was extremely naïve thinking the naming process would be easy…asthe decision took on a 16-month life of its own. We initially contracted with Interbrand, a highly recommended New York firm that took on the assignment under the code name “Project America.” With an eye toward Michael’s vision of incorporating an educational component, Interbrand’s assignment was to recommend a list of names to properly position “The New American College Town.” The company ran four focus group sessions in New York and Chicago, and presented their work covering a wide variety of 122 names, from which it recommended 19:

Antares New Vista Gateway Solus

Odyssey Ventura Horizons Landmark

Osceola Meridian Frontier Crystal City

Aurora Solaris Rainbow Majestic

Golden Oberon Jubilee

Disney’s legal team researched each name, knocking out those that were unavailable or had use restrictions — including many of our favorites. We decided we needed another consultant and engaged Lippincott & Margulies (L&M) – another hot-shot New York branding guru. We added L&M’s list to the prior possibilities, and along with names we got from all other sources, our own contests, focus groups, polls, etc., we ended up with a frustrating master list of 264 potential names. We were all getting frustrated. Peter e-mailed me: “I’m at a loss. It’s the damnest problem I’ve ever seen. Not sure how to proceed.”

We then engaged the Disney Development executive team and selected eight names to be tested — one more time — in focus groups at EPCOT.

New Century Landmark

Hyperion Maderia

Disney Springs Ameritown

Fantasia Jubilee

Even that effort didn’t produce consensus, and the Disney Development team labored on. Michael visited us in early 1991, and Peter, Todd Mansfield (a key member of the DDC team) and I took him, and Jane his wife on a tour of the OMUD property. Stopping at the location where Town Center was to be built, Michael asked, “What are we going to name this place?” We gave a brief overview of the process over the past 16 months, ending with Todd stating that “we have a list, Michael.” The final names under consideration?

Horizons

New Vista

Dimensions

Ameritown

Celebration

The final approval to proceed with the project came in an unforgettable phone call. From Orlando, Todd and I spoke with Frank and Larry. The transportation deals and other aspects of the project were coming together, but Frank was being very hesitant giving the final Approval of development of the Town. I was very assertive that I would not proceed with those deals and the formal announcement of the project without a firm approval that it was going forward.

Wells said, “You will if I direct you too, though, right?”

“No, Sir” I replied firmly. And the final approval was given.

On April 29, 1991, we appeared before the Osceola County commissioners, business leaders and other elected officials and publicly announced Celebration. On May 6, 1991, we filed an Intent to Use Application with the U.S. Trademark Office to register the name CELEBRATION. On May 28, 1991, the Application for Development of Regional Impact was signed by Todd Mansfield and filed. The Osceola County Commission approved the initial DRI on March 23, 1994. We broke ground May 18, 1994, 25 years ago. The first family, the Habers, moved in on July 1, 1996.

Andres Duany, who made great contributions but wasn’t ultimately part of the final design team, wrote in 2004 that Celebration was “one of the most intricate and accomplished examples of urban development since the 1930s.” In the end, he wrote, Celebration must be assessed the way all urbanism should be assessed — not by photos and short visits (which suffice for architectural criticism), but by inhabiting a place for a period of time. Does the community improve how the day is lived? Does it accommodate the ebb and flow of life?”

Disney, which sold its ownership of Celebration in 2004, no longer is involved with the community, with the exception of several commercial sites, and a few residential tracts. But Celebration still reflects the years of planning, process and research that went into it — and the vision and advocacy of Peter and Michael.

Andres’ questions, I feel, are being answered — positively.

Tom Lewis is an attorney, an architect and retired Colonel in the U.S. Air Force. In Orlando, he was the architect for the Orange County Civic Facilities Authority, monitoring the expansion of the Tangerine Bowl, being constructed by Standard Steel Industries; project architect for the Major Realty Office Building, Cypress Woods Condominiums, the Florida Center Bank, and state office buildings downtown. He served as chairman of the City of Orlando Zoning Commission and vice chairman of the city’s Planning Board, and at the state level as assistant secretary of the Florida Department of Transportation and secretary of the Florida Department of Community Affairs. He became vice president of Disney Development Company, for Community Development, and led the planning and design team for the town of Celebration, Disney’s groundbreaking residential development.